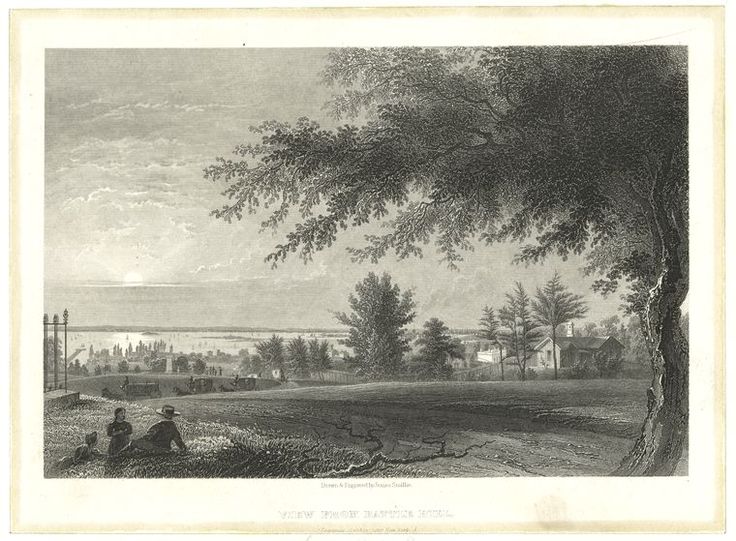

This charming engraving is by James Smillie (1807-1885). James Smillie was from a whole family of artists and engravers–so many that I had a hard time telling them apart (it doesn’t help that they all have maddeningly similar names).

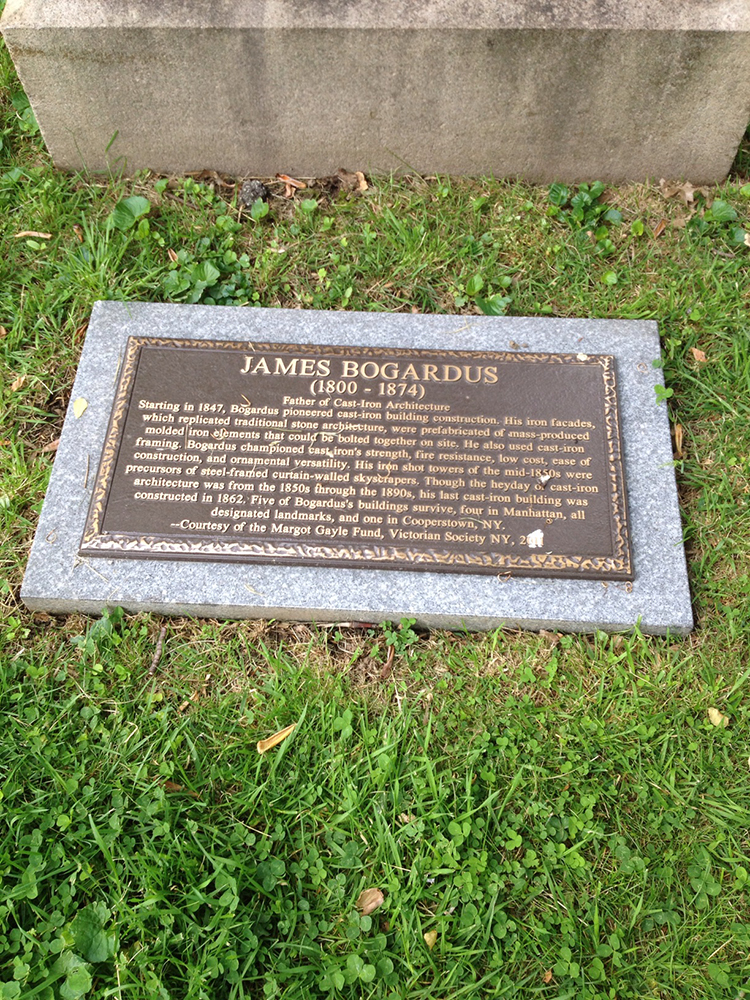

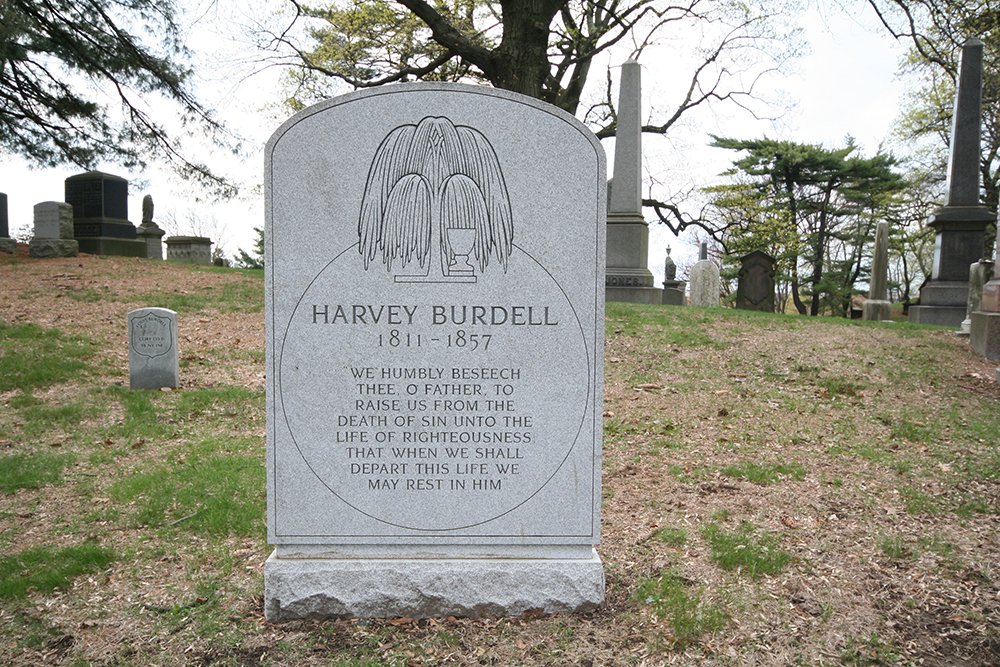

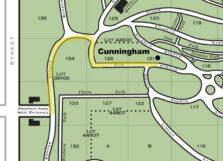

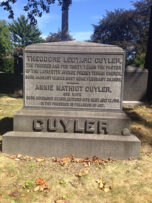

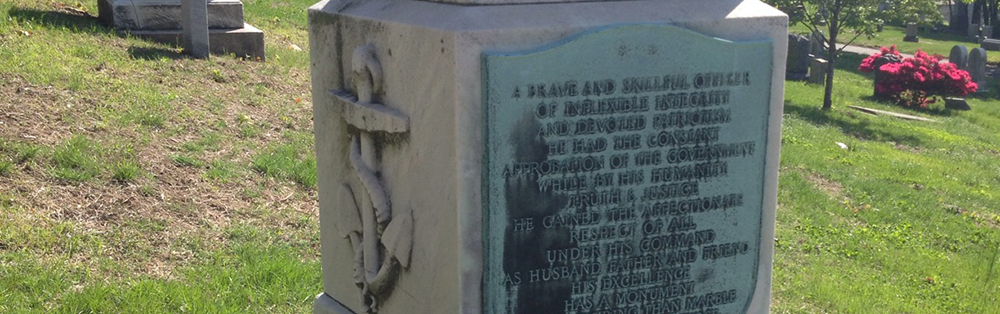

Here is the Smillie family plot, which I found–as usual–by wandering around and taking photos of anything that looked mildly interesting.

James Smillie, a native of Scotland, ended up in New York City in 1829, at the age of 22. His father was a jeweler in Quebec, and he sent young James to London and Edinburgh to learn silver engraving so that he could work in the family business. James’ talents were clearly more along the lines of drawing and etching, so he left Quebec after only a few years and struck out on his own in New York City. Within three years of his arrival, he was an admitted into the prestigious National Academy of Design.

James Smillie created the illustrations for the first written history of Green-Wood, Green-Wood Illustrated, which was published in 1846. According to historian Jeff Richman’s blog on the Green-Wood web site, he may have used the money from these illustrations to buy this large family plot.

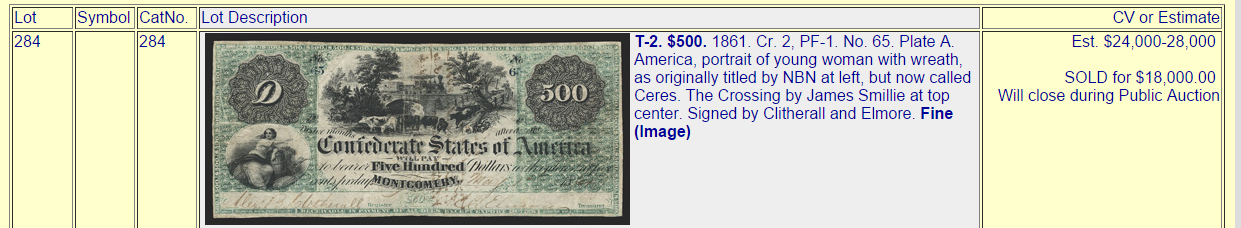

Later in his life, James Smillie devoted himself to designing and engraving bank notes. In fact, from what I’ve read, almost every male member of the Smillie family worked as a bank note engraver at one time or another.

Check it out, I found one of his bank notes online at a stamp auction. $18,000!

James and Catherine Smillie had four children. Two of their sons, George Henry (1840-1921) and James David (1833-1909) were also well-known artists/engravers.

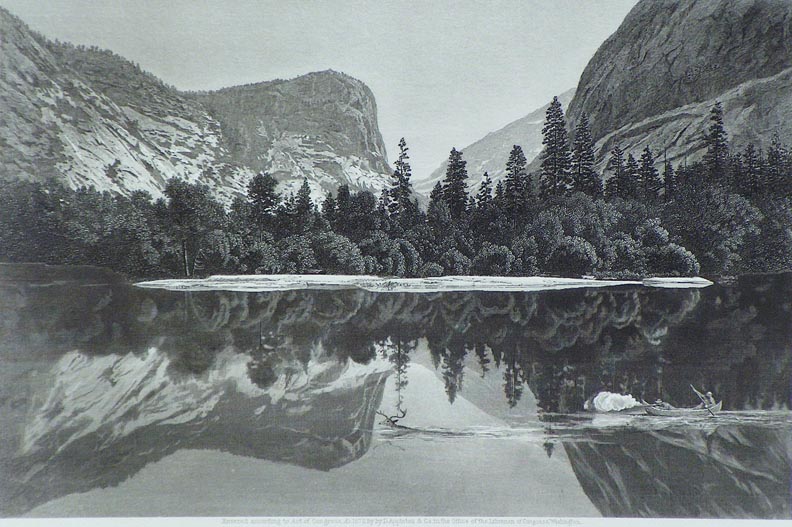

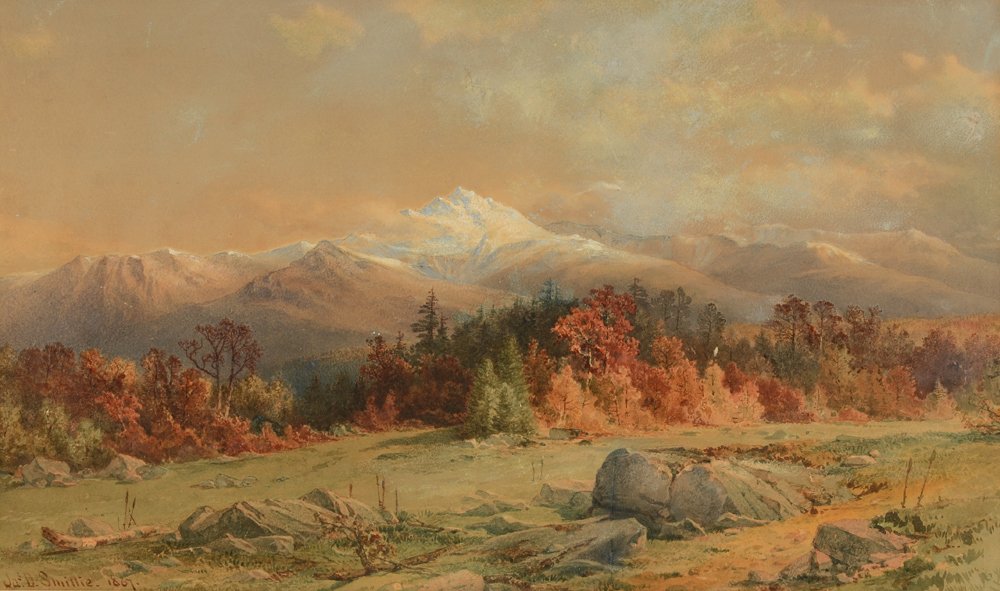

James David Smillie was trained by his father in the art of engraving starting at around age 4. They worked together on many projects, and he spent much of his professional life working as a bank-note engraver. His true passion, though, seemed to be drawing and painting landscapes.

His work is beautiful and meticulous:

He liked painting landscapes and traveled a lot in California and Colorado, painting mountain scenes.

James D. Smillie was also one of the founding members of the American Watercolor Society, and served as one of its first presidents. He taught for over 30 years at the National Academy of Design. His work is in the collections of many museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

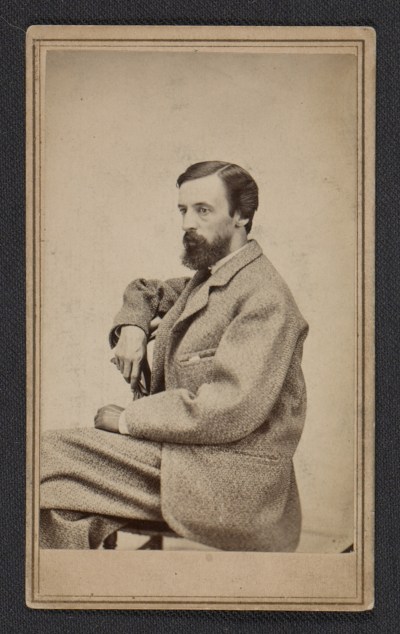

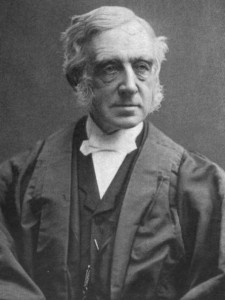

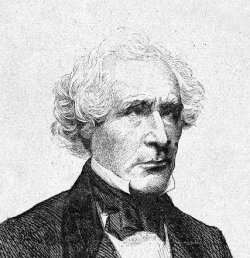

He married in 1881 in his late 40s, and had 2 sons. Here’s a picture of him:

James’ brother George Henry Smillie was an equally successful artist. He studied with famed Hudson River School artist James McDougal Hart, who is also buried in Green-Wood. (OK, now I have to find him as well). Unlike his brother, George stuck mostly to the East Coast, painting quiet country landscapes and coastal scenes.

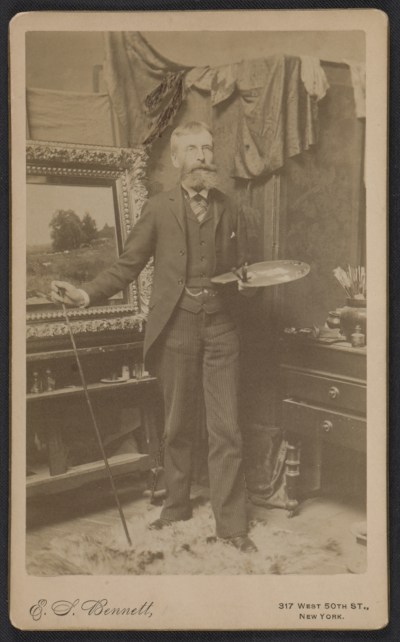

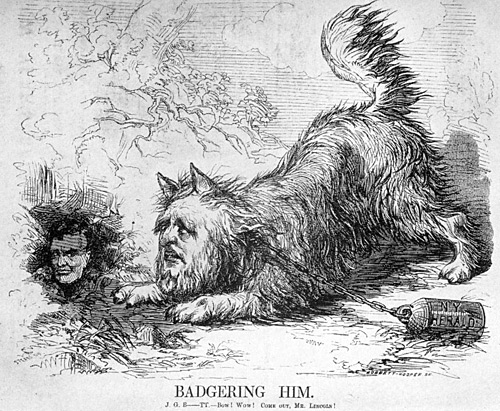

Here’s a picture of George working in his studio. This photo is hilarious–after all, who doesn’t like to paint while wearing a 3-piece suit?

George’s wife Helen “Nellie” Sheldon Jacobs (1854-1926) was also a painter–they shared a studio on East 36th Street in Manhattan. He met her when she was one of his brother James’ private pupils. Here’s a picture of her from 1887:

And here’s one of her paintings:

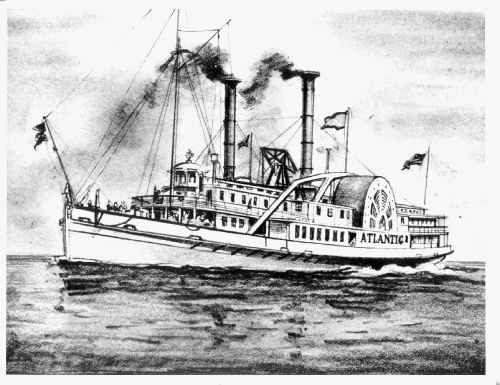

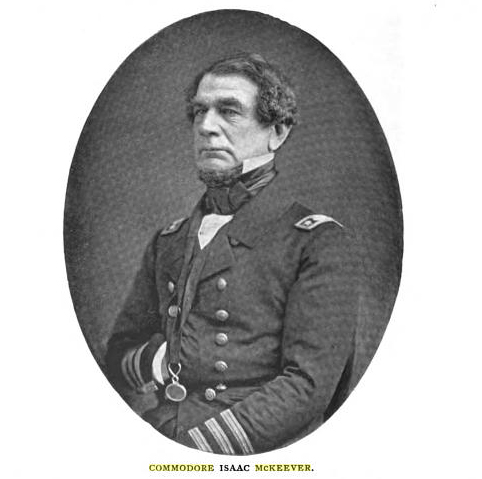

Isaac McKeever joined the navy in 1809 (at 18 years old) as a midshipman. By the time the War of 1812 broke out, he had become a Lieutenant. In 1814, McKeever was commanding a gunboat on Lake Borgne in Louisiana, when the British forces attacked.

Isaac McKeever joined the navy in 1809 (at 18 years old) as a midshipman. By the time the War of 1812 broke out, he had become a Lieutenant. In 1814, McKeever was commanding a gunboat on Lake Borgne in Louisiana, when the British forces attacked.