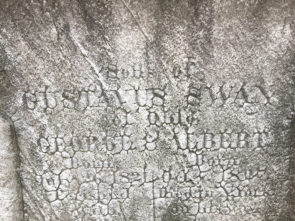

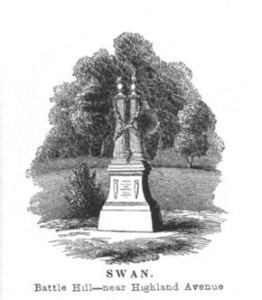

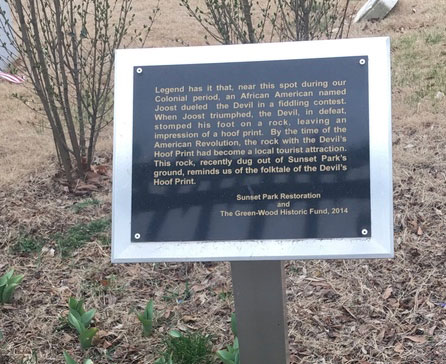

Another little gem I found in Nehemiah Cleaveland’s A Directory for Visitors was the site for brothers George and Albert Swan.

This took a little searching, but I eventually found it.

George and Albert Swan were the sons of Gustavus Swan, a prominent Ohio lawyer and Ohio Supreme Court judge. Both lived in Ohio and attended college at Harvard. George was killed on his way there via the steamship Lexington on January 13, 1840. Albert got sick and died 5 years later in New York, also en route to Harvard. Apparently, commuting to Harvard is hazardous for your health.

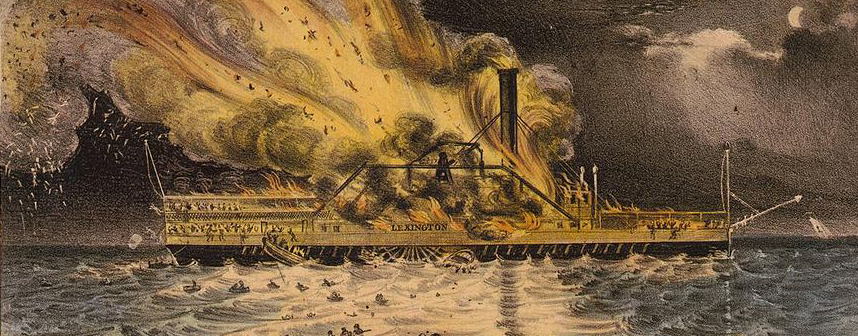

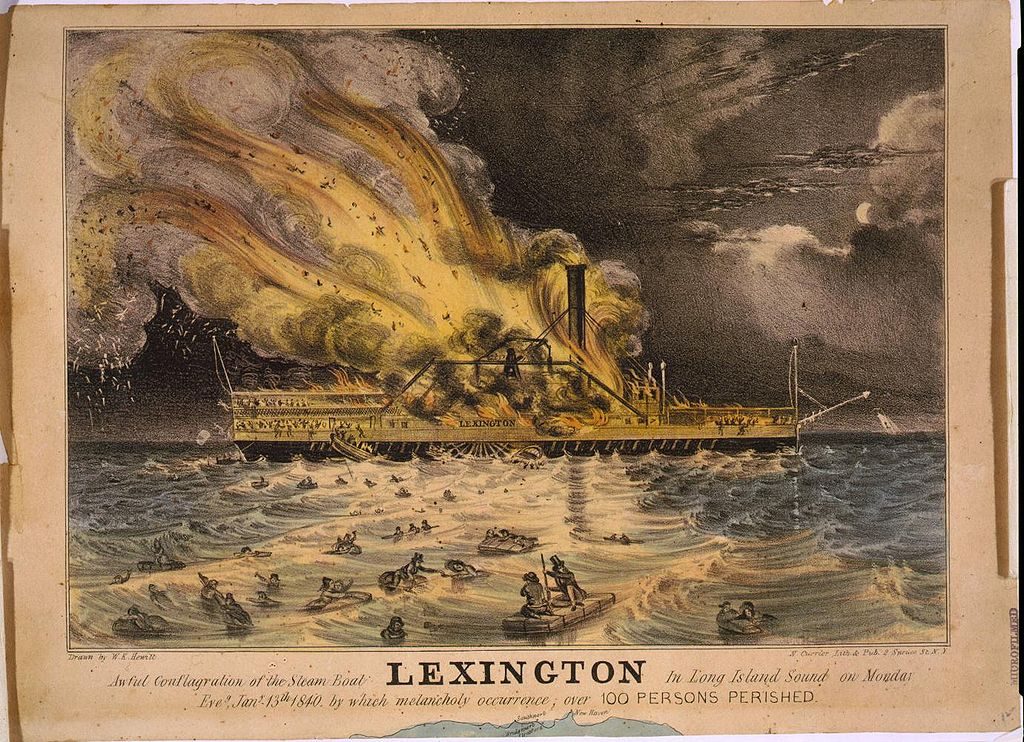

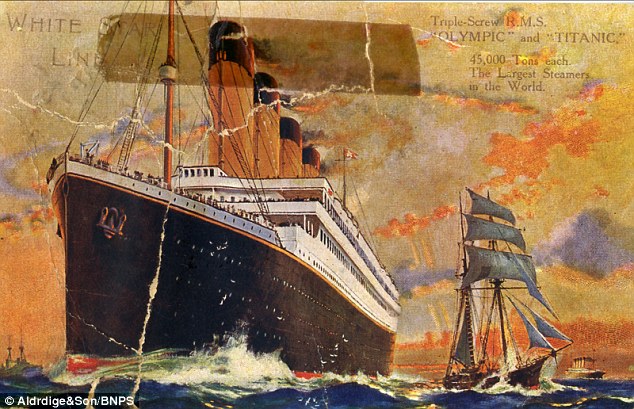

George’s death aboard the Lexington must have been horrific. The Lexington was a steamship that ran a route between New York and Connecticut, traveling along the Long Island Sound. It caught fire and sank off the coast of Long Island, killing all but 4 of its 164 passengers and crew.

The Lexington had been commissioned by famed billionaire Cornelius Vanderbilt, and was designed to be fast and luxurious. The ship could make the trip between New York and Providence in an unprecedented 12 hours, and would often have celebrated racing competitions with other steamships.

It was eventually sold to another company, and the ship’s wood-burning engine was converted to coal–a conversion that clearly was unsuccessful.

On the cold January evening when the ship went down, the Lexington was burning extra coal to aid in its struggle to get through the frozen, choppy waters. This proved to be too much for the engine, and around 7pm, the overheated smokestack caught fire. The fire quickly spread to the ship’s cargo of bales of cotton, and the Lexington went up in flames. All lifeboats that were lowered were quickly sunk–some crushed by the ship’s paddlewheel–leaving passengers and crew to drown, burn, or freeze to death. HORRIBLE.

A few random notes about this:

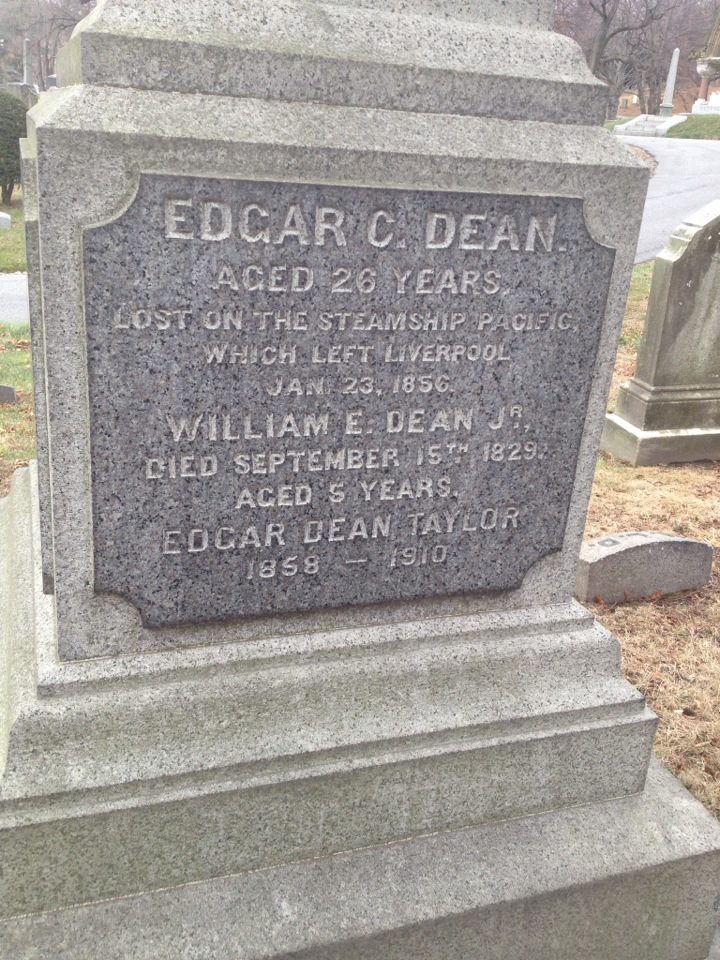

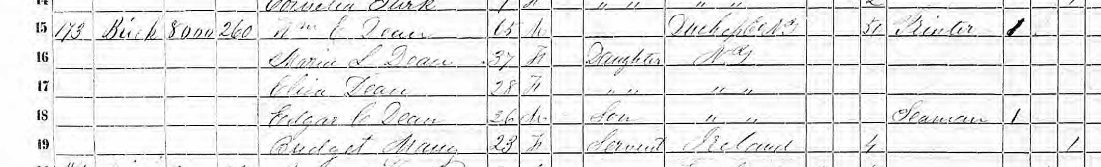

–Hidden treasure: A man named Adolphus S. Harnden was aboard ship, carrying a large amount of money, $18,000 of which was in gold and silver coins. He was one of the last people to go down with the ship. It is said that the gold coins are still there on the bottom of the Long Island Sound, but the silver ones would have deteriorated.

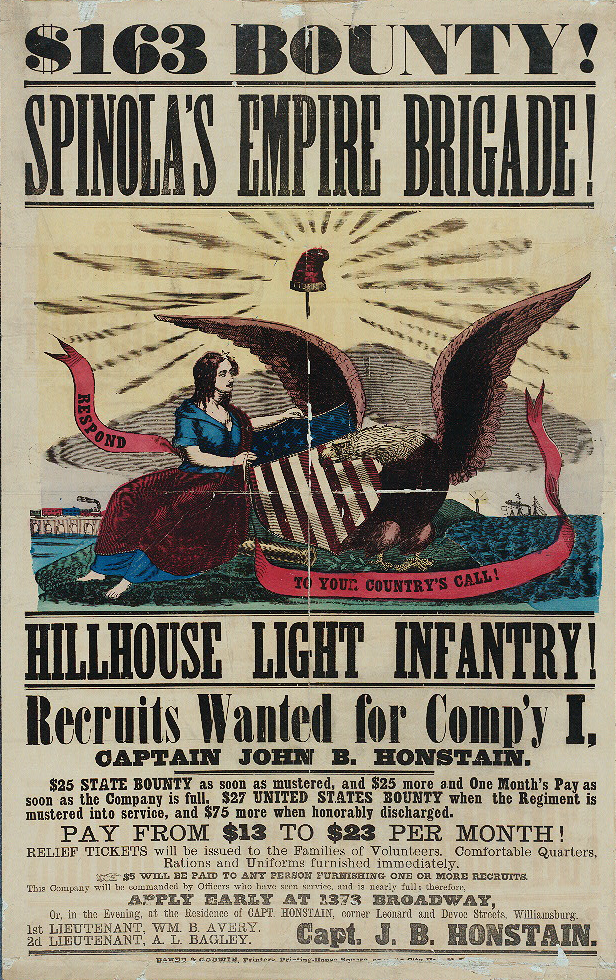

–There was a ship only 4-5 miles away that could have come immediately to the rescue–but the captain of that ship, Captain William Terrell, wanted to stay on schedule and refused to respond. He was criticized sharply for this decision by the press, and was publicly shamed–to the point where he was advised not to venture out in public. An article in the New Yorker opined, “Human language fails to express properly the feelings everyone should have at the utter stupidity of such a man.”

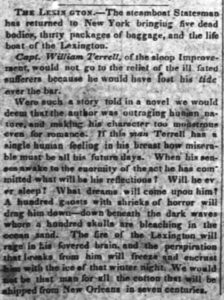

And here’s a clip from The Times Picayune, criticizing him all the way from New Orleans:

–Only four people survived, one of whom was the ship’s pilot, Stephen Manchester. After climbing aboard a makeshift raft that sank, he managed to pull himself and a passenger up on a bale of cotton. He used his knife to cut holes in it for his arms so he could hang on. Despite Manchester’s heroic efforts, during the night, the passenger slipped off the bale and drowned. Manchester floated on the bale of hay all night long in the freezing water, and wasn’t rescued until noon the next day.

–Another survivor was second mate David Crowley. He too managed to climb on to a bale of cotton. He drifted for over 43 hours before coming ashore 50 miles down river. He then walked a mile to a nearby home, knocked on their door, and immediately collapsed.

—The Awful Conflagration of the Steamship Lexington was one of the first lucrative prints that Nathaniel Currier (also a Green-Wood resident) sold. This image was so popular that Currier’s presses ran continuously for several months producing copies. Prior to this print, Currier had focused on more sedate imagery, and his business had not been much of a success. The Awful Conflagration of the Steamship Lexington showed him that there was profit to be made from images of disasters, and he began to make more. It was then that his business truly took off.

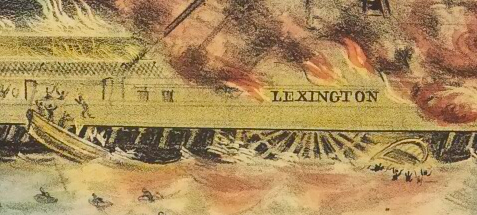

–A couple attempts to lower lifeboats resulted in the boats getting sucked into the paddlewheel and crushed to bits. One of those boats was full of passengers. If you look closely at Currier’s lithograph, you can see that he has included this detail: