Barney Williams (1824-1876), nee Bernard O’Flaherty, moved to America from Ireland in 1831 when he was just 7 years old. This was an interesting time to be in New York City–the Erie Canal had just been completed, and the city’s population and economy was growing quickly. Immigration was also dramatically on the rise. From Virtual NY:

In the 1830s New York City was in the process of attracting large numbers of poor Europeans, including a massive wave of Irish immigrants seeking relief from British colonial rule. (Between 1830 and 1850, the foreign-born population of New York grew from 9% to 46%.)

Many of these Irish immigrants settled in to the notorious Five Points neighborhood, which is where young Bernard and his family ended up.

It sounds like he had a delightfully scrappy youth. Bernard, a.k.a., Barney, took a number of odd jobs to make extra income for his family. Most famously, he worked for Benjamin Day’s startup newspaper The Sun as one of the first newspaper boys. Actually, I read in a couple of places that he was THE first newsboy, and that for a while he was THE ONLY newsboy, but I don’t know how accurate that is… At the very least, he was one of the first and prototypical newsboys, known for standing on streetcorners shouting, “Extra! Extra!”

Another one of his odd jobs was working at the theater. One night while working at the Franklin Theater, an actor in the cast of The Ice Witch fell ill and the then 14-y.o. Barney took his place.

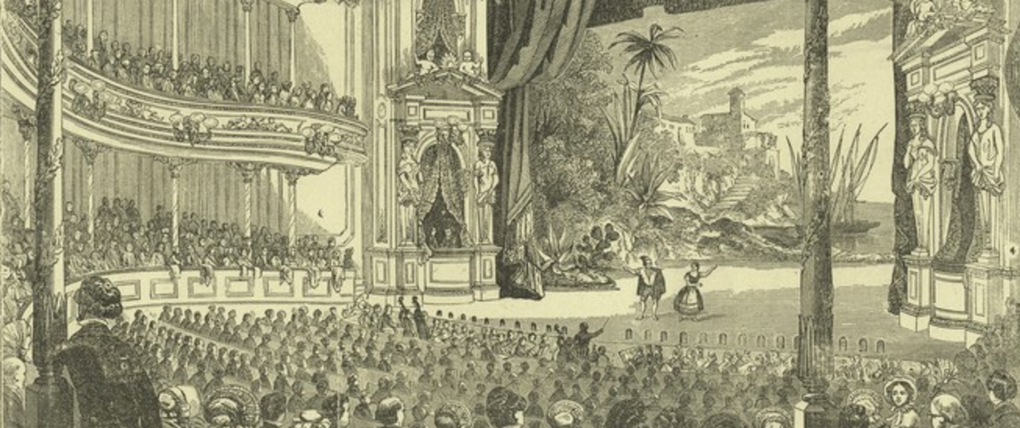

I could not find out much about either the Franklin Theater or The Ice Witch, but I did find this image of Niblo’s Garden–a large, famous theater in which Barney and his wife Maria would later stage many productions. And while Niblo’s Garden was huge compared to most theaters at the time, this should give you some idea:

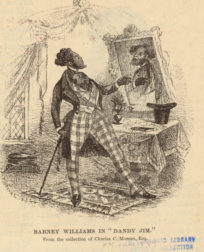

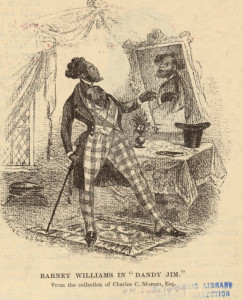

Barely a teenager, Barney then embarked on a long and quite successful career in the theater. He sang, he danced, he was a comedian, and he even did a couple of seasons in “Kentucky Minstrel”–also known as BlackFace Minstrel shows. Here’s a playbill from one of his productions:

He was only 19 years old at the time.

Barney married actress Maria Pray (1825-1911) in 1849, less than a year after her husband, comedian Charles Mestayer, had died. Maria was from a show-biz family: Her father William Pray was an actor who had died in a theater fire in New York some years earlier, and her sister Malvina was married to the famous actor William Florence. A talented singer, dancer and actress in her own right, Maria had joined the corps de ballet at the Chatham Theater in New York (located just south of the Bowery) when she was only 15.

According to History of the American Stage, by Thomas Allston Brown:

“On Nov.29, 1850 [Maria Pray] was married to Mr. Williams, and from that day can Mr. Williams date his rise in the profession; for not until they started together was he recognized in the profession as of any account.”

Soon after wedding Maria Pray, Barney Williams was considered the top Irish actor working in America at the time–a title that had previously been held by his mentor, the famous Irish actor, writer and producer Tyrone Power (1795-1841).

Barney and Maria became huge stars. They starred in numerous plays, musicals, and vaudeville acts together–too numerous (and often too obscure) to name here. They also wrote and produced their own plays–always centered around Irish characters and themes. “The Irish Boy and Yankee Girl,” “Ireland As It Is,” “Shandy McGuire,” and the comic opera “Rory O’More” are just a few of their starring productions. With a burgeoning Irish population in America, these productions were enormously popular.

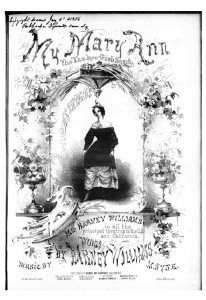

In 1856, Barney wrote a song called “My Mary Ann” for Maria. It was one of the couples’ most beloved songs.

Here they are in a production together:

Maria and Barney traveled a lot and enjoyed a long and happy career–they spent several years in the U.K., and performed for the Royal family three different times. They performed for–and likely met–Abraham Lincoln in 1863. They were also–naturally–enormously popular in Ireland. When Barney died of a stroke in 1876, his estate was valued at a whopping $400,000.