A few weeks ago, I volunteered at Green-Wood’s table at the grand re-opening of Teddy Roosevelt’s birthplace in Manhattan (which is a whole other story). And while I was there, I met Trish Mayo who was also volunteering. We got to talking, and she knew a lot about Green-wood and the history of New York. She said she likes to wander around the cemetery taking pictures, and when she sees something interesting she goes home and looks it up. I was like, “SEPARATED AT BIRTH” and of course tried to rook her into writing for my blog. And it worked! Here’s her first entry.

THE FIRST AND AMONG THE LAST

No matter where I go I seem to end up finding graves, sometimes I’m not looking for them they just are on my path to somewhere else.

Recently, I traveled to Boston and decided to spend a day in nearby Concord, MA–home to Louisa May Alcott, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau and Nathaniel Hawthorne. Concord is also the site of the first battle of the American Revolution fought on April 19, 1775. The battle is commemorated in Minute Man National Park.

There’s a reconstruction of the wooden bridge where the British and American soldiers met:

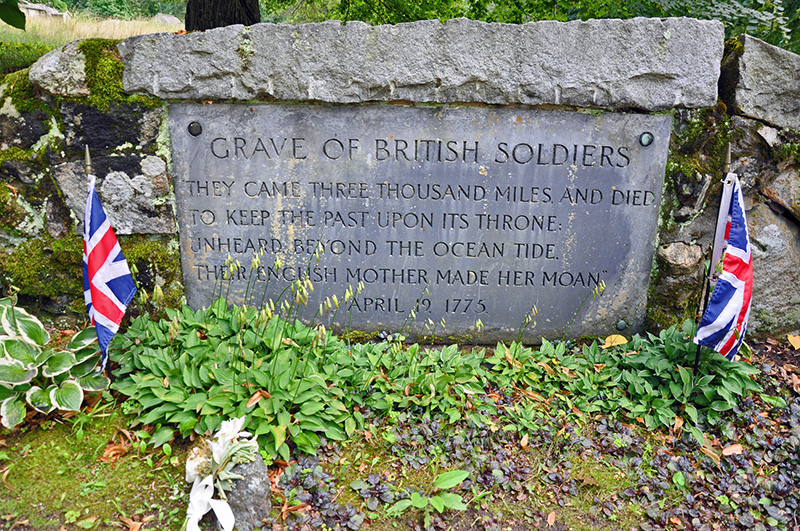

What I didn’t expect to see was a grave for 2 British Soldiers killed on that day in 1775:

The inscription reads:

They came three thousand miles and died,

To keep the past upon its throne.

Unheard beyond the ocean tide,

Their English mother made her moan.

From the poem “Lines” by James Russell Lowell

According to the park’s website “British military records indicate that there were three soldiers (all privates in the 4th Regiment) missing and presumed dead after the North Bridge fight: James Hall, Thomas Smith and Patrick Gray. One of these three men is buried in Concord center; there is a stone marker for him on Monument St. The other two are buried here.”

These 3 soldiers James Hall, Thomas Smith and Patrick Gray are among the first casualties of the War for Independence. The people of Concord arranged for their burial and later erected this monument to mark their final resting place.

A few weeks later, I’m back in New York and decide to go for a walk in Green-Wood Cemetery. I locate a group of headstones that predate the founding of the cemetery. That’s not uncommon, for various reasons churches and congregations decide to move and arrange for the headstones and graves to be relocated to another cemetery. While reading these old headstones I see the word “Rhinoceros” and think, what’s that all about?

The inscription reads:

To The Memory of Edward Morley, Late Master of His Majesty’s Ship Rhinoceros who departed this life on August 8, 1783

The only reference to the HMS Rhinoceros that I can find is that it was a store ship and used as a floating battery in defense of New York towards the end of the American Revolutionary War. The war ended with the signing of the Treaty of Paris and the Treaties of Versailles on September 3, 1783, less than a month after this man’s death on August 8, 1783. The last British troops left New York City on November 25, 1783.

For this man to have died so close to the end of the war makes this marker and the story it tells especially poignant. There’s no mention of how he died – I can’t find any reference to battles or skirmishes that would have involved his ship near the August 8th,1783 date, so the question is, was he gravely wounded in battle? A victim of disease or an accident?

So there you have it two Revolutionary War graves, hundreds of miles apart but bookmarking the beginning and the end of America’s struggle for independence. What makes them amazing is that they are memorials to the other side in that conflict – British soldiers and a British sailor still remembered over 240 years later and given a final resting place in the country that was formed from the conflict that cost them their lives.