For Christmas this year, one of my presents was the book Green-Wood, a Directory for Visitors by Nehemiah Cleaveland. Cleaveland was the first historian of Green-Wood (and eventually a resident of course), and the author of Green-Wood Illustrated in 1847. He published this little book in 1850. It’s essentially a self-guided walking/carriage tour of some of the earliest sites in Green-Wood–along with some helpful illustrations.

One of the first illustrations and stories in the book that caught my eye was for The Pilot’s Monument:

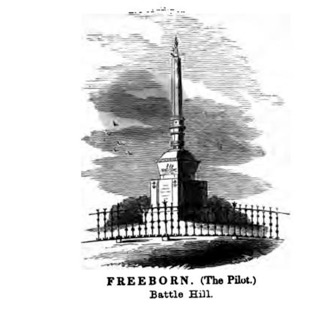

So I set out to find it. Cleaveland’s directions are pretty confusing, but the one thing he did mention is that this monument sits high up on a hill so that it can be seen from the harbor by other pilots. So I ventured up to the top of Battle Hill on a rainy winter morning, and lo and behold, I found it.

By the way, one of my favorite Green-Wood residents James Smillie created a lovely lithograph of how this monument must have looked back in the day:

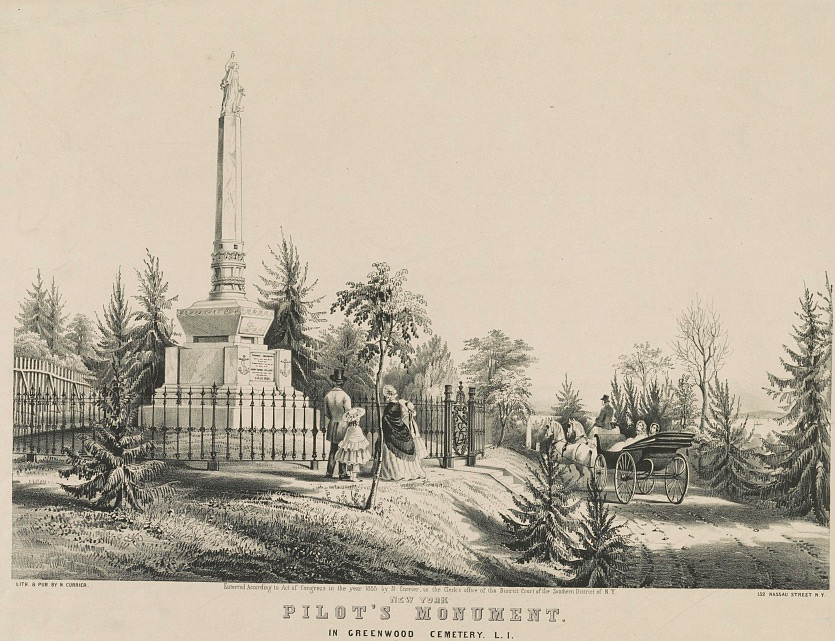

This must have been a popular attraction; here’s another depiction, this time by another Green-Wood resident, Nathaniel Currier of Currier & Ives fame:

The Pilot’s Monument is the final resting place of Thomas Freeborn (1808-1846). Freeborn was a nautical pilot. The Pilot’s job was to guide ships into the harbor, expertly navigating that area’s waterways. Pilots didn’t work on a particular ship–they worked in a particular harbor. Their job was to board approaching vessels and bring them safely to shore.

Freeborn worked the harbor in Mantoloking, New Jersey. On February 15, 1846, he was guiding the John Minturn into harbor when a violent Nor’Easter hit. This was a tremendous storm–the worst that region had seen in over two decades. At least nine ships were lost that evening, but the most dramatic and heart-wrenching was the wreck of the John Minturn.

The John Minturn was considered a “Packet Ship”–this meant that it carried U.S. Mail and other parcels, as well as a modest number of passengers. At the time of its sinking, John Minturn was carrying about 50 passengers and crew, 40 of whom perished that night–including Freeborn and the ship’s captain and his family.

The ship was not far from shore when it sank; in fact, when it finally went down it was only 300 yards away. Unfortunately, the storm and the choppy seas made it nearly impossible for any rescue efforts to reach the ship–despite the fact that they tried for over 18 hours. As a result, the John Minturn‘s final terrifying hours were witnessed by hundreds of stunned onlookers who had gathered on the beach throughout the night. The horrified crowd could do little other than watch as the ship went down in the frigid waters and frozen dead bodies washed up on the shore.

The New Jersey Scuba Diving Association has this chilling account from one of the rescuers. Here are some excerpts:

“At eleven o’clock at night with the storm still raging the Minturn went to pieces. We could hear the wailing shrieks that went up from the despairing ones, as the sea at last caught them in its merciless embrace. The cold was intense, and when the bodies came to in the shore, many were found frozen as rigidly as statues. Quite a number, I recollect, struck the beach in a sitting position, and thus we saw dead men sitting as upright as in life, as we drew them out of the way of the waves.”

“When day broke again, we saw the bow of the boat still remained intact and a group still huddled together upon it. One mother could be seen, with her babe clasped to her breast, her hair streaming in the wind, and her white face turned upward in prayer, appealing to Him who ruled and ruled above the war of the elements. When this section broke up, it was found that every one of the group had been dead for many hours.”

“Those on board were not idle. After several attempts and failures, two sailors entered a boat with a rope, and put off for shore. The current carried them so swiftly to the southward, that they were compelled to cut the rope, to save themselves from capsizing. They came safely ashore with the last boat, and found it impossible to return.”

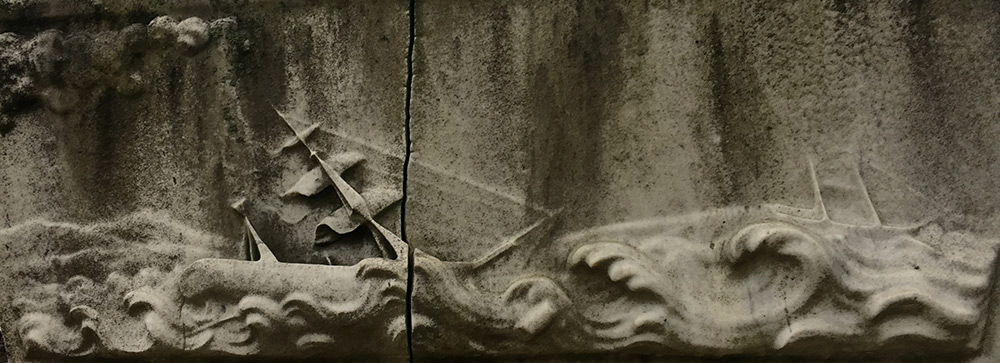

I find this last story particularly interesting because if you take a look at the monument, you can see the severed rope, just above the depiction of the shipwreck: