From “The Penny Press”. A Brief History of Newspapers in America:

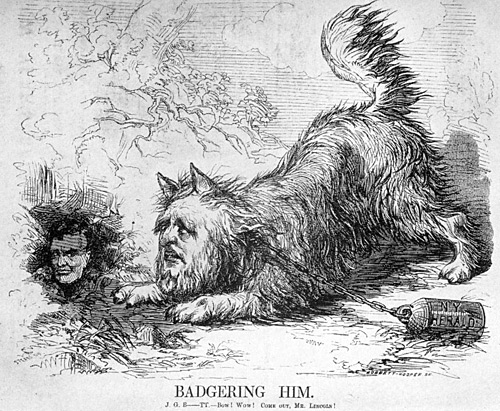

“James Gordon Bennett’s 1835 New York Herald added another dimension to penny press newspapers, now common in journalistic practice. Whereas newspapers had generally relied on documents as sources, Bennett introduced the practices of observation and interviewing to provide the stories with more vivid details… Bennett reported mainly local news, and corruption in an accurate style. He realized that, ‘there was more journalistic money to be made in recording gossip that interested bar-rooms, work-shops, race courses, and tenement houses, than in consulting the tastes of drawing rooms and libraries.’ He is also known for writing his ‘money page’ which was included in the Herald and also coverage of women in the news. His innovations made others want to imitate him as he spared nothing to get the news first.”

Bennett was also a sharp critic of Abraham Lincoln, who was elected President in 1861 at the height of The Herald‘s popularity. Bennett was in and out of favor with the Lincoln Administration throughout the Civil War; at one point he donated a yacht to the administration, in exchange for insider information and favors (such as a cushy position for his son).

The Herald also detailed the comings and goings of Mary Todd Lincoln, who was vacationing one summer in Long Branch, New Jersey. Bennett assigned a charming and socially wily millionaire named Henry Wikoff to ingratiate himself to Mrs. Lincoln and her Society pals. The regular column, “The Comings and Goings of Mrs. Lincoln” was all ridicule of the First Lady at the beginning–but that changed quickly when she started writing letters personally to Bennett in response. They struck up an unlikely friendship, and Bennett realized that he could garner favor and gather inside information by changing the tone of this column to one of flattery (almost to a ridiculous extent). At one point, Wikoff was able to charm his way in to Mrs. Lincoln’s inner circle and steal an advance copy of Lincoln’s Congressional address, which was then published by The Herald.

(On a side note here, Henry “Chavalier” Wikoff sounds absolutely fascinating. He was born into great wealth, and spent his entire life traveling, writing, hob-knobbing with the rich and famous, and of course romancing the ladies. His relationship with Mary Todd Lincoln was the subject of a lot of scandal at the time.)

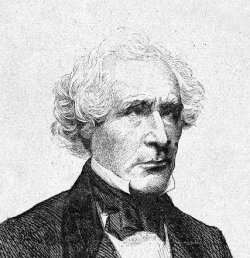

Bennett was known as a workaholic who spent endless hours obsessing over the news at his desk, which was built out of two barrels and some planks of wood (love that). A native of Scotland, he had a thick Scottish brogue, and his eyes were severely crossed. He married Henrietta Crean in 1840, just five years after founding The Herald.

The monument is lovely, but very sad–it shows a mourning woman kneeling in front, and a seemingly gravity-defying statue of an angel releasing an infant into the heavens. On the front, you can see two young children listed: Cosmo Gordon Bennett, who was five, and three-month-old Clementine Bennett. Sad.