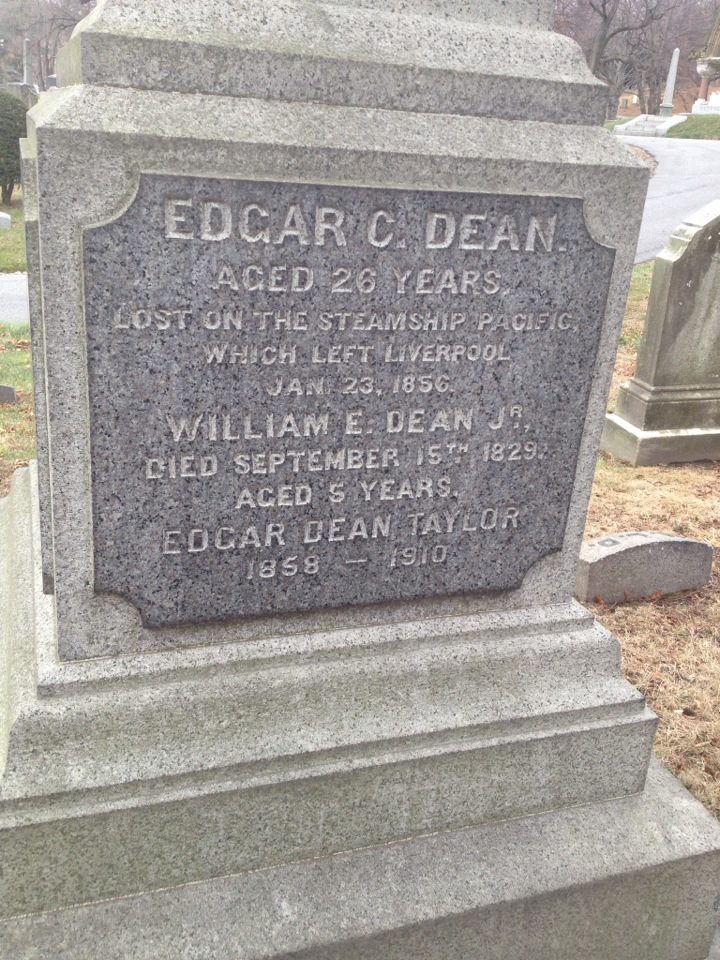

This was the headstone that gave me the idea to start writing this blog in the first place. I took this picture in February of 2013, when I first started exploring Green-Wood. As usual, I was wandering around aimlessly, and didn’t bother to keep track of where I had been. As a result, I have not been able to find this headstone again (of course). I’ll find you again one of these days, Edgar C. Dean!

Edgar C. Dean, 26 years old, sailed on the Steamship Pacific on January 23, 1856 from Liverpool. That much we can gather from the stone. I did some digging, but there wasn’t a whole hell of a lot I could find out about young Edgar or his family.

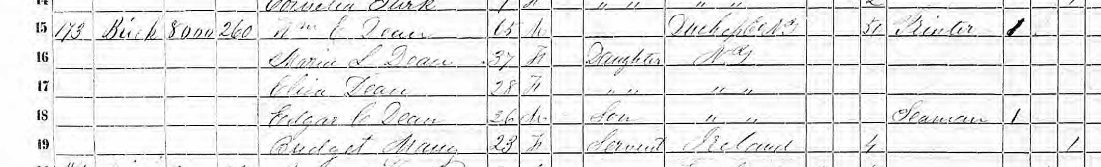

An 1855 census lists him as living with his father, two sisters and an Irish servant in downtown Manhattan. His occupation is listed as “seaman”.

His father, William E. Dean, was a printer. His business was located at 72 Frankfort Street, just down the block from Tammany Hall. As far as I can tell, the Dean family home was nearby on Church Street.

The ship that Edgar was lost on–the Steamship Pacific–was built in 1849. This ship was large, luxurious, and fast: in 1850 she broke the record for fastest transatlantic crossing.

From Sandman Cincinnati:

She spanned 281 feet and was powered by two precision side-lever engines, each with a 95 inch cylinder traversing a massive 9 foot stroke. At full bore, she delivered 13 knots with all four boilers in service and consumed up to 85 tons of coal a day. The passenger compartments were just as impressive. They were spacious, finely trimmed and furnished with steam heat, an innovation of the day. The ship had many amenities to suit the passenger’s needs including bathrooms, smoking rooms, a barber shop and even a french chef in the kitchen. The reason for the elaborate extras was to compete with Britain’s Cunard line. The SS Pacific and her three sister ships, Atlantic, Arctic and Baltic, were financed by the US government and specifically built to win back America dominance in transatlantic traffic. Together they made up the new Collins Line – a small group of larger, faster, and more comfortable passenger vessels.

Here’s where it gets interesting: On January 23, 1856 the SS Pacific and all 189 people on board vanished without a trace. Most assumed that she had hit icebergs off the coast of Newfoundland due to the fact that it had been a particularly cold and iceberg-filled winter. However, five years later, a beachcomber walking on the shore of Hebrides Island in Ulst (Scotland) found a message in a bottle from a British sea captain who was a passenger on the ship.

The note inside read:

On board the Pacific, from L’pool to N. York. Ship going down. (Great) confusion on board. Icebergs around us on every side. I know I cannot escape. I write the cause of our loss, that friends may not live in suspense. The finder of this will please get it published,

WM. GRAHAM.

A message in a bottle. Six years later. Well how do you like that.